Author: Thomas Fuster (Neue Zürcher Zeitung)

The diaspora plays an important role in the financing of development and emerging countries. However, it has received hardly any attention for decades in the field of development cooperation. Too much attention was given to allegedly more important projects. However, migrants, who usually retain a close link to their country of origin, have been coming to the fore over the past years. And there is a good reason for this: Around 200 million migrants worldwide, who regularly support their families in low or medium per capita income countries, constitute a great development potential. Such a potential should be used.

Expensive money transfers

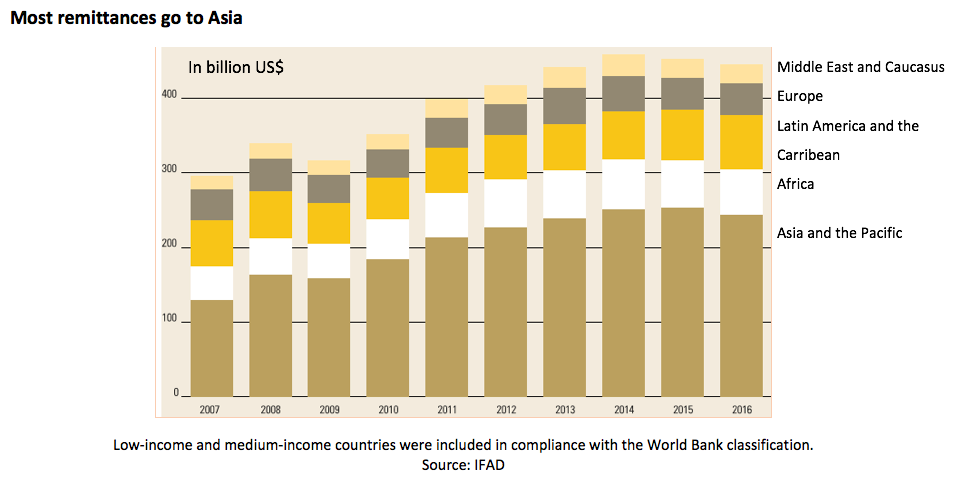

Large amounts are involved. A report of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) indicates that since 2007, remittances increased by 4.2% p.a. on average to 445 billion US$. That is three times more than the overall development assistance. Asian countries prevail among beneficiary countries. However, in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Kosovo, remittances constitute at least 11% and 15% of GDP respectively. An increase in remittances since 2007 is thus certainly astonishing, considering the financial crisis from that period. Migrants obviously prefer to limit their own expenses rather than to reduce the remittances they send to their families.

Remittances are frequently sent through informal channels. In the Balkans, for example, bus drivers frequently operate as money couriers. High transfer costs are a common characteristic of these numerous channels. Although these costs have largely decreased over the past 20 years, namely from more than 15% to 7.5%, they are still far from the target of 3%, defined by the UN Sustainable Development Goals, especially given the fact that these costs have been barely decreasing over the past years. However, should the decrease to 3% be achieved, beneficiaries would dispose of around 20 billion US$ additional funds per year. An enormous potential for improvement is particularly present in case of South Africa, where costs amounting to 15% are among the highest ones.

In beneficiary countries, the value of migrant contribution is known; in many of them there are separate ministries competent for the diaspora. However, donor countries, such as Switzerland, are also increasingly interested in it. The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) thus aims at targeted promotion of migrant potential for sustainable development in the framework of its programme ''Migration and Development''. According to Markus Reisle, programme manager, it is primarily about an improvement of framework conditions, in order for the experiences and money of migrants to be as effective as possible in their country of origin. The focus is on one's own initiative and responsibility. Reisle also gives an example: Migrants are frequently interested in investing in a business in their country of origin. However, if a country does not have a land registry for the entry of land title or if an administration is corrupted, it becomes difficult, given the fact that there is no investment security. Political dialogue is thus used to attempt to resolve relevant obstacles or initiate concrete pilot projects – such as, for example, a contact point for investors. All of this always includes the competent ministries and the diaspora, but attempts are also made to strengthen their organisation and resources. It has nothing to do with charity or altruism, says Reisle. ''Investments have to be profitable, it is about business models.''

SDC has been providing support to the platform ''i-dijaspora'' over the past two years. The association that operates in Switzerland wishes to support the development of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The potential is substantial. There are more than 60,000 persons of Bosnian and Herzegovinian origin living in Switzerland. Last November, a business forum was organised in Zurich. It gathered companies from the housing sector in Bosnia and Herzegovina and potential investors from Switzerland. An initial evaluation is quite positive. Five investors have, namely, already submitted concrete offers in the meantime, and in addition to this, four companies also visited their potential partners in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Start-up support from the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO)

One of the few diaspora members from Switzerland, who already does business in Bosnia and Herzegovina, is Edin Dacić. As a five-year old, he emigrated to Switzerland with his parents. After having completed his studies at the University of St. Gallen at the end of 1980s, he decided to try his luck in the Balkans. The company he established, Daccomet, today operates in the furniture industry and is a supplier of the Swedish furniture producer, Ikea. The company in Bosnia and Herzegovina already has around 400 employees, and the second plant in Serbia has 300 employees. Dacić frequently sends his employees to trainings in Switzerland, especially given the fact that the educational system in Bosnia and Herzegovina still has not really recovered from the war.

Dacić is also a Steering Committee member of ''i-dijaspora''. What is his motivation? First of all, he would like to raise awareness. The State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) namely has a start-up fund intended for companies in transition countries, which he benefited from himself as well. However, diaspora members barely know about such assistance. Secondly, in his opinion, a lot would be achieved if at least a small part of remittances would be channelled in investments instead of being only used for consumption. ''The reason for this is the fact that large corporations will continue to steer clear of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the future; the engagement of the diaspora therefore becomes even more important.''

Source: Migranten als Entwicklungshelfer, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 29.01.2018.