Bosnian Emina Smailbegović is a writer and the youngest doctoral student at La Sapienza University in Rome

Emina Smailbegović was born in 1996 in Sarajevo. She spent her childhood and elementary school days in Breza. Although she comes from a family of mathematicians, as a girl she discovered a talent and love for art - she began to write her first stories and learn to play the piano at the Elementary Music School in Breza. Listening to classical music and many hours of piano practice and reading various readings have become her daily routine.

Because of her dedicated work, Emina's parents decided to support her dreams and her decision to continue her musical education in Tuzla. At just 14, she left the safety of the family home and stepped boldly into the world. During her high school music education, she met professor Aida Muharemagić Gavrilova, one of the best pianists in the former Yugoslavia. Working with the professor and learning from her left a big mark on Emina's later musical journey. Encouraged by the professor's support and advice, she decided to study music and leave BiH.

In 2014, while still in high school, Emina applied for an exchange program and a scholarship. After passing the entrance exam at the Venice Conservatory of Music, she officially began a three-year piano study.

„It wasn't easy to move to a new environment, to live in a different culture. But the habit, perseverance and attachment to music helped me get used to it quickly. At the Conservatory I met people like me. People who share the same passion for music and want to go to concerts and to the opera house. It's much easier when you're surrounded by people your age who have the same interests. It helps you make the new environment your new home."

After graduating with a degree in piano and a master's degree in musicology, Emina realized during her internship at the Institute of Music at the University of Vienna that she wanted to continue her research and enroll in doctoral studies. With the help of her professor Antonio Rostagna, whom she met during her master's studies, she spent a year diligently preparing for the difficult entrance exam at the University of La Sapienza in Rome. Out of more than 80 applicants, in the end she was among the first three admitted students and thus, at the age of only 24, she became the youngest doctoral student at the famous La Sapienza University in Rome.

The focus of Emina's doctoral research is the analysis of reception and musical tastes after the French Revolution:

„I want to explore what has changed and what opera arias were performed in the houses of the bourgeoisie, which were born in that period. These are music collections from the beginning of the 19th century that are located in Genoa, Venice, Verona, Parma, Florence, Vienna. I have already visited cities in the north of Italy and collected the necessary data, and currently I am doing part of my research at the Vienna Institute of Music as a PhD visiting student.“

Beginnings of writing career "VIA APPIA"

Inspired by Venice (and everything experienced until then), Emina started working on her debut novel "Via Appia" in 2016, at first thinking it would be a short story. When the writer and columnist Andrej Nikolaidis read the first manuscript, he told her that what was written must be published. She listened to him and the novel was published in 2019.

„I believe there is hard work behind writing. I think these are processes and I think it comes through reading. For good writing you need to read well first. With work and research, your style, sentence, details that determine everything and by which you will be recognizable will be formed. While writing the novel Via Appia, it happened subconsciously," explains Emina.

Via Appia is the oldest road in Europe and one of the oldest ancient Roman roads connecting Rome with the south and southeast of Italy. It is a route that led from Rome to Brindisi, a port facing the Adriatic coast and towards “our” part of the world. The main character of Emina's novel, Kozimo Meštrović, will take the path that connects the past and the present.

Emina explains that Kozimo is going back in time because he, like her other characters, is not very enthusiastic about the future:

"Kozimo does not look to the future with joy. He is, in fact, tormented by the past. It depicts the relationship of postmodernity, that is, the time in which we live and in which these characters are, against modernity and everything we know today that modernity is and it is disordered. Even if they have not experienced war directly, my characters, like us in reality, carry deep wounds. Kozimo is aware that he cannot change anything because the past is impossible to change ”.

In her debut novel, Emina weaved her conviction in such a way that it is unlikely that some great revolution or some incredible change in society will save us from suffering. Change rather begins in and with ourselves:

"I am more for perseverance and for doing as much as we can for ourselves and on ourselves. Everyone is obliged to work on themselves as much as possible, and if that happened, then we could expect some big and important change in society. Without it, there is nothing. My writing, for example, specifically contributes to our language and our literature. And I'm not the only one, there are a lot of young people who are great. They have the capacity to elaborate cultural ideas and creativity that I have not seen in people who are, for example, my parents' generation."

Older generations and the media, says Emina, often unjustifiably attack young people, say ugly things about them and accuse them of being apathetic, sluggish and disinterested:

"It is more pronounced in BiH, but there is such an opinion in Austria and Italy, Germany and Spain. I am also critical, I criticize myself and my colleagues, but criticism should be constructive. In my second novel, The Terrible Children of Averroes, there are three parts to a philosophical lecture, and in one of them, a professor of philosophy, who is already in his sixth decade of life, admits that they (the elderly) do not understand our world. He admits that he accuses us and has a desire to understand us, but not just like that, he works pro forma. The professor admits that our worlds are different."

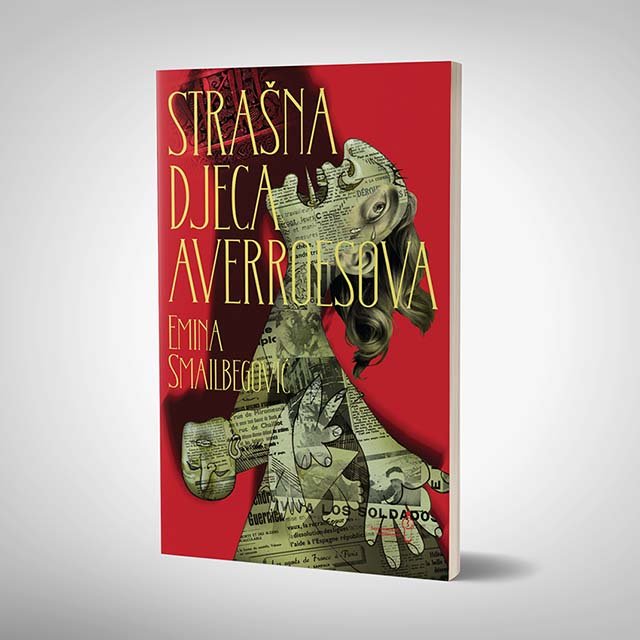

"The Terrible Children of Averroes"

At the end of March 2022, Emina published her second novel "The Terrible Children of Averroes", in which we follow two parallel actions. One of them is set in the Middle Ages, and the other in 2019. In a medieval setting, we follow the characters of the famous Islamic philosopher Averroes and the rhetorician Aksa. The characters of philosophy professor Jordi and archaeologist Celia are placed in a contemporary context. The past and the present, says the author, are connected "on the basis of mimesis, mythology, philosophy and archeology, because these are universal things that are always the same and that live on today."

One of the main characters after whom the novel is named is Averroes (or Ibn Rushd), a philosopher who wrote reviews of Aristotle's metaphysics and debates, and was an expert in jurisprudence and Islamic law, medicine and theology. As one of the few who knew ancient Greek in Europe at the time, Averroes managed to revive interest in Aristotle's thought among Western philosophers and lay the idea and foundations of European rationalism. His fate, however, was tragic - he contracted Parkinson's disease and was persecuted, and then his entire oeuvre was burned and forgotten both in Europe and in the Arab world. In the novel, the author of Averroes frees and saves difficult destinies:

"My idea was to write a novel about identity, about how complex and fluid it is, about how much we really are at the same time. This partly includes philosophy, but Averroes and his lectures are only part of a novel that has its own plot.

The part of the story set in (our) present that follows the former lovers of Jordi and Celia ends tragically. Their two, like Kozimo Meštrović, no longer find anything in the present, and bear the burden of their parents and the past, which they cannot get rid of and which, having chosen philosophy and archeology as their vocations, they do not want to get rid of. That leads them to misfortune. Like Cosimo, the two were not directly involved in the war, nor were they divided by the Jordi's Francoist beliefs and Celi's Republican stance - the past defined them differently.

In the novel and that part of it that is set in modern times, the brilliant members of society are despised. This is a consequence, notes Emina, of the status that philosophy, like classical music, has and the belief that they are reserved only for the sophisticated elite and aristocracy.

"There is a big gap because of the academic community. These are not topics reserved only for certain individuals and these are stereotypes, when we say that someone cannot understand philosophy or classical music. Dealing with philosophy does not mean just sitting on books and studying a particular author, his thought or interpretation. Philosophy, like classical music, is important for life, it should help us and society in particular, and it never exists for its own sake. They came from man and society and should be brought as close as possible to people. As in any other thing, when you understand them, then they are no longer far away from you and you have no aversion to them."

Plans for the future

In the near future, Emina plans to continue working on her research, write a doctoral thesis, teach piano, enjoy opera. She does not want and does not hope for instant success. Everything she does, she will continue to do without haste and allowing things to go naturally and in their course. She does not plan to return to Bosnia and Herzegovina because she believes that there are many more chances in Italy or Austria to continue doing what she loves. She would love to continue living in Rome because she loves Italian art, diversity, aesthetics and classical music.

Wishing her, with a lot of luck and success, to continue writing in words and expressing in music her knowledge of the world, when asked about the message for young people, Emina answers:

"Young people don't like to be advised, but if I have to, then I would tell them that it seems better to be wise than educated in life (and I don't mean just having a degree), but that's not the case. I would also say that they should think about culture because it can only make them free and critical of the world. I would tell them that I think it is worth learning and that it should not be stopped. And I would add that we all have to face difficulties, but that it is better to face them today and immediately, than to serve an opinion that is not ours all our lives."

Become a member of our network!

Note: Copying parts or the entire text is allowed with the obligatory citation of the source.

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay up to date!