As a formative figure of the renewal movement of the Black Wave, Zafranović reinvented the genre of the Yugoslavian partisan film with his cult film Occupation in 26 pictures: Against the background of the lush Mediterranean scenery, he contrasted the joie de vivre of a happy youth with the arrival of evil by fascism and the resulting disintegration of society. Zafranović stands with its films full of life and lurking disasters against the forgetting of its own history. And so, in his apocalyptic iconoclasm epic The Decline of the Century (The Testament of the L.Z.), completed in exile, he leads dialectically from the historical shots fired in Marseilles to the present day in the 1990s.

The Stadtkino Basel is very pleased to welcome the Dalmatian maestro personally in Basel in November! For the first time in Switzerland, it is showing the most important works of this obsessive cinematograph in a ten-part retrospective.

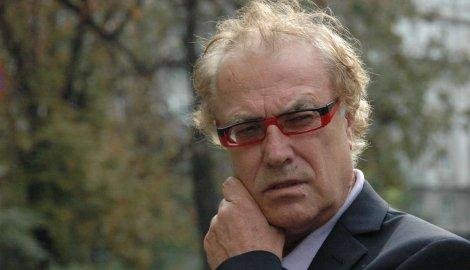

Dalmatia and Lordan Zafranović

With Lordan Zafranović the Stadtkino Basel honors one of the greats of Yugoslavian cinema. But whoever now expects the usual Balkan clichés or partisan westerns has made a mistake. Zafranović is a highly political author. His home is Dalmatia, the beautiful eastern Adriatic coast with its offshore islands. Dalmatia - that is the Mediterranean of the Greek-Latin culture with its heroic and divine legends. These are Venetian city castles with Italian-speaking patricians and Slavic hinterland. This is Catholic crusadery in the fight against Byzantine-Ottoman conquerors. In 1918 Dalmatia joined the newly founded Yugoslavia, today it belongs to Croatia.

Lordan Zafranović visualizes the Dalmatian way of life intensively and virtuously. He captures the people in their everyday life, observes their habits and the effect of the Mediterranean midday heat on their minds. He is interested in situations where good times break away and lead to catastrophes, and does not shy away from looking at the roots of evil: like Greek godfathers' legends, such times put people to the test and reveal the core of their being. Because of his incorruptible, humane state of mind, Zafranović had to leave his home country when the Yugoslavian wars broke out in the early 1990s. His films disappeared in the bunker - today they enjoy cult status.

Opus

Eighty films and the collaboration on well over a hundred scripts is the opus of this obsession with cinema. This natural talent began his film career at the age of 16 in the Split Cinema Club, where he spent his childhood and youth after the Second World War. With an 8mm camera he experimented with image and sound, space and time. Even then, the short-sighted man developed his unmistakable formal signature with the help of pattern recognition and focus adjustment.

In 1966 Zafranović changed to the professional field and moved to Zagreb. He became the co-founder of the legendary self-administered Film Author Studio (FAS) around producer Kruno Heidler. The result was the impressive, formally completely different black and white short films Nachmittag (Das Gewehr) and Passanten 2, both of which belong to the Black Wave of Yugoslavian cinema. This highly innovative and at the same time socially critical cinematic movement of the 1960s and early 1970s, which includes Dušan Makavejev (W.R. - Misterije organizma, 1971) and Aleksandar Saša Petrović (Skupljači perija, 1967), was sharply controlled by the state censorship authorities, as it held up a mirror to the political system.

Prague and color

Zafranović first opened up the opportunity to study at the Prague film school FAMU with Oscar winner Elmar Klos. In his first feature-length film for the big screen, Sonntag 2, he lets six people drift in the style of the Nouvelle Vague through an only seemingly boring Sunday in his hometown Split in 1968/69. While making love, buying cigarettes and having lunch, they meet all kinds of bizarre contemporaries until they finally hijack a bus and race through the city in a wild chase. In the highly politicized period after the suppression of the Prague Spring, Zafranović also got into serious trouble with the censorship. Awarded top marks in Prague, the Croatian censorship authority labeled Sunday 2 a "black film" and imposed a performance ban.

Now Zafranović went for the color. In Waltz (My First Dance), a skillful and mischievous homage to the legendary dancing master Juti from Split, he turned the inner world of thoughts of his protagonists to the outside with grotesque means. In the course of a ball, flowers, scars or even a cutlet grow out of the dancers' faces. In the same year he shot Ave Maria (My First Drunkenness) for the first time on the island of Šolta, in his birthplace Maslinica. The sun and the church bells structure the hard life of the fishermen and shepherds. A little shepherd boy quenches his thirst with wine in the shimmering heat. His goat does not survive the drunken furor of little Bacchus. The censorship authorities promptly saw in the red, dead animal an attack on the Communist Party and banned this film as well.

Zafranović, Kovač and David

In Croatia with a de facto occupation prohibition, Zafranović tried its luck in the Yugoslav capital Belgrade. The meeting with the dramaturge and writer Filip David proved to be fateful. David introduced him to the legendary literary circle around the internationally celebrated writer Danilo Kiš, who at the time commuted between Belgrade and France. This included Mirko Kovač, whose works have long been classics of Serbian and Croatian literature. In him Zafranović found his congenial script partner. In the Belgrade coffee houses, the artists' circle discussed Sartre's existentialism as well as the failure of the youth movement and the question of how to put a stop to the nationalism that was already spreading in the Yugoslavian Federation in the 1970s. Zafranović, Kovač and David were looking for a suitable material to warn the Yugoslavian public by cinematic means. They worked closely together until the end of the 1980s and created the director's central masterpiece, the "War Trilogy" with Occupation in 26 Pictures (1978), The Fall of Italy (1981) and Evening Bells (1986).

From different perspectives and formally very different, the three works illuminate the disintegrating effect of the German-Italian occupation of 1941-1945 on society as well as the responsibility of the communist revolutionaries in resistance and new beginnings. The images that Zafranović found for Occupation in 26 pictures to translate the warning of the return of nationalism into the visual, leave no one cold. Against the beguilingly beautiful backdrop of Dubrovnik, the audience follows the fate of three spoiled young friends of Croatian, Jewish and Italian descent. When their everyday life and the Dubrovnik society is torn apart by the fascist German-Italian occupation regime, the three have to take a stand. The epic, based on the memories of a Dubrovnik lawyer as well as archive documents, exemplifies the destructive dynamics of imperialism paired with nationalism and racism, which fuels hatred and violence and divides society and families. In The Case of Italy, Zafranović once again shoots on Šolta. Partisan commander Davorin (Daniel Olbrychski) has to decide whether the end justifies all means, whether the higher goal stands above private happiness. The script is based on archive material and the war memories of the amateur actors. In contrast, Evening Bells focuses on a revolutionary (Rade Šerbedžija) who is guilty of inciting fratricide. The film adaptation of the successful novel Vrata od utrobe (1978), which was filmed in Ćilipi near Dubrovnik, is also the chronicle of a young man who moves from the rural idyll of Herzegovina to the big city.

Trilogy

Occupation in 26 pictures was shown in 1979 at the Séléction in Cannes and became the most successful Yugoslavian film of the year, as well as in Czechoslovakia. The director's refusal to cut a merciless, central scene of a massacre in a bus cost him an Oscar nomination. "Everyone is responsible for their own path in life," is the recurring message at Zafranovićs. If he had bowed to the producers' demand, the inner construction of the film would have been destroyed and the film would have lost the effect intended by the authors. Because of the depiction of Italian war crimes in the eastern Adriatic, The Fall of Italy at the Venice Biennale in 1981 triggered a fierce polemic among Italian film critics. In 1982 he was awarded the Grand Prix of Valencia. Evening Bells won the Golden Arena for best director at the Yugoslavian film festival in Pula in 1986, but was classified by the censors as anti-communist and has hardly ever been shown abroad.

Decline of the Century

In the first free elections in Croatia in 1990, Franjo Tuđman became president, who relativized the war crimes of the fascist Croatian Ustaša state NHD 1941-1945 and made its symbols presentable again. Soon after the outbreak of war in 1991, he had Zafranović, who had been intensively involved with the Ustaša concentration camp Jasenovac since the mid-1980s (Krv i pepeo Jasenovca, 1985) and who had filmed the war crimes trial against Andrija Artuković, the former Ustaša state interior minister extradited by the USA, declared a traitor to the country in 1986. The quarrelsome director, who had also been actively involved in politics during these years, fled, carrying with him the rough cut of his new film. While in exile in Paris and Prague in 1992 he followed the horrors of the Croatian and Bosnian wars on television, he edited the film into a powerful, unsparing and formally completely independent treatise on Croatia's fascist past. The Decline of the Century (The Testament of the L.Z.) (1993) is a masterpiece of European cinematography about the tragedies of the 20th century. At the same time it is an indictment of the historical-revisionist policy of the Croatian president Tuđman and his supporters. A broad public discussion of the film is still not possible in official Croatia. Zafranović, a prominent figure in the entire former Yugoslav region, a kind of public conscience that clearly expresses what many do not dare to do for fear, remains a persona non grata in his Croatian homeland. However, as Jasna Nanut of the Croatian Association of Directors writes on the occasion of his 55th professional anniversary in 2019, the rediscovery of this great figure of Croatian and Yugoslavian cinematography is inevitable there as well.

Prof. Dr. Nataša Mišković

This retrospective is part of a project sponsored by the Fund for the Promotion of Teaching and Research of the Voluntary Academic Association FAG, which also includes a course at the University of Basel. We would like to thank our co-curator Nataša Mišković, who made this series possible in the first place.

Source: stadtkinobasel.ch